BACK

Xinjiang – A Region Under Siege (Our Repressed History)

by Jean Castorini & Pailey Wang / 5/2/2021

On the 19th of January 2021, in the dying days of the Trump administration, the US State Department declared that the repression of Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region constituted genocide and crimes against humanity. The position was quickly endorsed by the incoming Biden administration. It was the strongest yet such declaration made by a state. A rare step that might see harsher sanctions and other countries follow suit. One year earlier, on that date, we were travelling through the region trying to come to our own understanding about the situation there. It adds to the growing condemnation of Chinese policy in the region, which has arisen since revelations in July 2020 about the forced sterilization programme being run in Xinjiang alongside the construction of new detention sites. The MEP Raphaël Glucksmann, last October, bemoaned the inaction of the EU. So much media coverage, public outrage and until now, political and diplomatic idleness since our departure from China.

It has been almost exactly one year since we parted our separate ways after three weeks travelling in Xinjiang. Parting at Guangzhou train station on the 31st of January 2020: On the bullet train back to Beijing and flying back to Paris, or via ferry to Hong Kong to fly back to Sydney. We were escaping the escalating COVID outbreak that we never imagined would follow us home.

Since our visit to the Autonomous Region in January 2020, a year ago, it would be an understatement to remark that the discourse on China has intensified and polarized. At the same time our means to pull reliable information about developments there are becoming ever scarcer. With correspondents for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and other foreign news outlets expelled from the Middle Kingdom in March 2020, as a result of the escalation of diplomatic tensions, reporting has been hampered. The field is now left only to a handful of rare, skilful journalists.

In spite of our numerous attempts to write down our experiences from three weeks travelling across the region, we have repeatedly failed to do so. Not only because of the difficulty of writing about this kind of travel which was envisioned to have neither a purely touristic nor journalistic purpose, but especially because of the difficulties in recounting, through words and photography, what has now come to increasingly be called a ‘cultural genocide’.

How to narrate, or cover, what we experienced and have come to call a region under siege? Where, under a well-orchestrated campaign of propaganda, intertwined with religious repression, life seems to go on; yet an omnipresent violence is palpable. When entering and exiting a city, one is required to go through a police checkpoint to verify their identity with a face scan and have their car searched. A region where the only ‘museums’ left standing (if such institutions can even be called museums) are near empty kitsch temples of propaganda, showcasing the now nearly completely suppressed Uyghur lifestyle and its past traditions. Where, like in a Tussaud’s Museum, wax sculptures populating staged theatre settings are the rare remaining testimonies of centuries of cultural identity. Where, on a boulevard, an illuminated billboard showcases continuously an image of Xi Jinping, who lives and governs some three thousand kilometres away from the region.

Recounting such anecdotes might appear grotesque, yet all evidence points to an ethnicity, its people and its culture, silently repressed. Worse still, a region in which multinational companies, despite the political circumstances, have decided to expand without any shame, even accommodating the state’s policy of religious and cultural annihilation. In December 2019 in an article titled ‘Inside Chinas’s Push to turn Muslim Minorities Into an Army of Workers’, the New York Times wrote “The Communist Party wants to remould Xinjiang’s minorities into loyal blue-collar workers to supply Chinese factories with cheap labor”. How can multinational companies turn their backs on such lucrative prospects? Xinjiang, a region of legalised, state sponsored slavery, accommodating your consumption, and mine. Are we then all cowards outside of China, continuing to consume blindly, not preoccupied by what the now usual ‘Made In China’ identification hides? It is we in democratic countries who have the agency to shout out while in Xinjiang most cannot, for their own survival, open their mouths.

The fate of the Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities in Xinjiang is not an issue which only concerns China. The globalisation of today’s economy and our dependence on imported products manufactured in China makes us all accomplices. A March 2020 research paper by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute identified “82 foreign and Chinese companies potentially directly or indirectly benefiting from the use of Uyghur workers outside Xinjiang through abusive labour transfer programs as recently as 2019” , including, among others, BMW, Bosch, ASUS, Calvin Klein, Volkswagen and Apple. The study found that between 2017 and 2019, an estimated 80,000 Uyghurs “were transferred out of Xinjiang and assigned to factories through labour transfer programs under a central government policy known as ‘Xinjiang Aid’ (援疆).” What is taking place in Xinjiang is an international crisis, and it needs to be acknowledged as such. As SupChina reminds us: “About 20% of the world’s cotton comes from China, and about 85% of that comes from the Uyghur region.”

Attempts to document Xinjiang have been frequently turned down: In November 2018, the acclaimed Chinese photojournalist Lu Guang, a resident of New York, went on a visit to the far Western province to meet with local photographers, and suddenly disappeared. It took a month and a half for his wife and family to be notified of his arrest by the local authorities. Though thousands of news articles are published online from abroad, what visual testimonies do we have of the ongoing repression? Nearly nothing. Only satellite images allow us to witness, passively, the replacement of shrines; cemeteries and old towns by concrete infrastructure.

What is happening inside what are referred to as ‘internment camps’ does not need to be seen to be believed. A simple stroll of the streets of different cities in Xinjiang suffices to grasp that things are not going as usual. The haunting emptiness of streets of Kashgar, the muteness of people all around the region during four weeks there, and the airport-like control of teens at metro station police checks are all disturbing hints of a whole population’s repression.

This is apparent in the provincial capital Urumqi, where the now closed mosque’ façade next to the Grand Bazaar displays Carrefour and KFC logos rather than a Muslim inscription at its entrance. Such is the tactic. If the mosque is not yet bulldozed or its minaret torn down, the rare few left apiece are sealed, converted in empty ‘museums’, or turned into shopping malls. The rare places of worship left are circumscribed by fences and accessible only via gates and identity checks.

In the centre of Urumqi, most condominiums' entrances are equipped, in addition to the usual and omnipresent security cameras, with face and ID scans in order to pass through the gated fences. Each entry and exit is monitored and restricted. In some apartment blocks, security employees even do the job of checking the identity of each person passing.

A few blocks away from the Grand Bazaar lies an imposing Mosque still open to worship. As visible as the mosque’s minarets is the pole in the middle of the courtyard on top of which flies a wide red flag of the People’s Republic of China. While we pass by, a few men are exiting the prayer hall via a narrow side street, under surveillance cameras.

Such seems to be the routine for the last remaining faithful, who still dare to practice publicly. Or rather the last allowed to do so. Yes, because where have all the others gone? In the city of Kashgar, located some fourteen hundred kilometres south of Urumqi, why is China’s largest mosque nearly emptied of its once large congregation? The city’s square in front of the Id Kah mosque is half deserted, the only life that remains is a desperate camel standing, waiting to be photographed with tourists. Other than that, only the coercive presence of policemen is guaranteed. Troops of four by four policemen walk in a highly orchestrated manner from one side of the square to the other, equipped with helmets and shields. On the corner of the square, the usual police barracks, with its distinct typology and blue and red lights on top, which make it even more visible. Camel, police with shields walking like robots, and I was forgetting, a skewer of old men, dressed in black, their canes in their hand, sitting in line on the edge of the forecourt, staring at the pale yellow facade and the two minarets of the 15th Century structure. Could this be some kind of surrealist painting? The square appears to us as rather underpopulated for its size.

“You came too late” tells us the manager on our return to the hostel, discreetly, as he points at a picture framed on the wall of the staircase leading to the basement. The photograph he shows us, taken during a Friday prayer in 2012 illustrates, outside the same mosque, another world. Thousands of believers in prayer cover the entire square.

Where have all the people gone? Where have the popular dances dissipated? Where have the musical melodies been lost to? Relics of past traditions seem to have survived only on the walls of the reconstructed old town of Kashgar. Here, a recent fresco, in a nearly deserted neighbourhood, echoes the dress and customs of the not so distant past.

We think about the few old men exiting the mosque and populating the edge of the square, who contemplated in calmness what is left to exist, when the majority of other places of worship have been reduced to rubble, or are on the list to be demolished. Less than a kilometre away from the Id Kah mosque, another one left standing has been overtaken by the crackdown. Barbed wire is strewn along the roof and security cameras have been installed on each side, more visible than the crescent moons themselves. On the front, above the main entrance, now sealed, can be read on a striking red banner: “Love the Party, Love the Country”. The usual Chinese flag is floating at the centre of the roof, atop the pole. On the street, passers-by are numerous, but none of them seems to be paying attention either to the slogan and the oppressive cameras nor to the mosque and its fate. The nightmare becoming reality is omnipresent and familiar to all.

We came too late, and the measures are in fact real. What is left in front of us is the debris of an ethnicity and its culture, shattered for years, and now struggling to survive.

The city centers of Kashgar and Urumqi have been turned into tourist fairs like those found in Beijing, Shanghai, and most other cities in China. Indeed, there are plenty of hotels on offer, and the natural parks are widely advertised by the authorities, with the aim of further converting the region into a domestic tourist destination. Imagine how nice it will be, when Xinjiang is populated by tourists in the same way that Georgia was frequented by Muscovites during the Soviet Union. Can you imagine?! Xinjiang and its breathtaking landscapes and natural environment could serve a market of more than a billion domestic tourists. Tianchi Lake would become the new Black Sea. Our first preview of this lake was on a giant billboard on our arrival at the railway station of Urumqi, with was adorned with a large slogan in English: “XINJIANG IS A BEAUTIFUL PLACE”, as if the region already had a sizeable population of English speaking tourists, to our great surprise. Consider not only the economic returns, in addition to the region's richness in raw materials, but the potential to move towards a singular Han identity, with Uyghurs remembered as a distant culture, of which the naan and the braised lamb on sticks would be the only remnants. The dunes of the Taklamakan desert as the rollercoasters, the crystalline water of Tian Shan’s lake and its surrounding valley as the ultimate summer resort and the UNESCO Tian Shan mountain ranges as the ideal winter sport resorts. The sun would glitter on the lakes surface and the quality of the ski resort infrastructure would leave little doubt as to what is occurring only a few kilometres away in clusters of standardized industrial concrete buildings skirted with razor wire.

Our (not so) fantasized Xinjiang

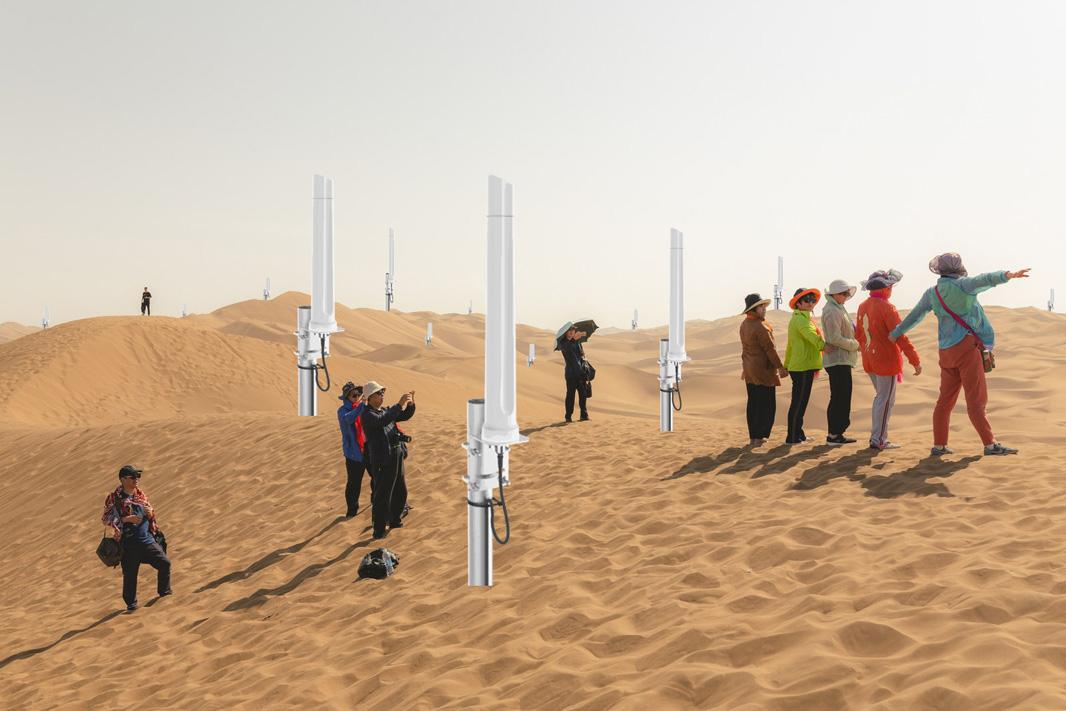

Xinjiang’s vast expanses of sand could serve as the location to host the world’s databases, when our lives become nothing more than digital identities, interacting through social networks and working remotely, from beyond our individual computer screens. Xinjiang will hence become a place of encounters, of the fast transmission of bytes and data, where our pixels will transition through the pixels of billions of other human beings interacting through the ether. The dunes would serve as fields where we might plant the seeds that sprout into 5G antennas, which in some distant future would become historic remnants of ‘nature’ that could then serve as tourist attractions; similarly to how the natural landscapes arouse the enthusiasm of tourists today, and in doing so deplete its very pristine sanctity. The graves and shrines bulldozed by the authorities to accommodate urban development, or to put it more accurately, to serve the process cultural and religious annihilation, could be repurposed into storage space for the hundreds of billions of images and videos shared on TikTok, WeChat or Facebook. Paradoxically, Xinjiang could from then on accommodate the digital memorialisation of the world’s billions of cats GIFs sent via social networks; the countless individual commercial transactions on Taobao (Chinese Amazon) as well as the GPS data accumulated from the tracking of the movements of the entire world population. Xinjiang would become the memory of the world, based on the annihilation of individual memory.

But, beyond this, and more importantly still, Xinjiang could become the new Hollywood, a Chinese Cinecittà with the capacity to host any of the biggest film productions, within a territory of more than a million kilometres squared (some three times the size of France), host to some of the most contrasting landscapes. A space that the Italian neorealists and Americans filmmakers of the twentieth century could only have dreamed of. With China’s film industry on the verge of topping the US as the world’s number one film market by box office revenue, the demand for the region and its locations will not be lacking. No need to reproduce sand dunes, cotton fields, lakes, forests and mountains! It’s all there. And, beyond the aesthetic advantages of the region, what an opportunity but to showcase the region through a myriad of screened fictions! But, is this really a future?

The shooting of the latest Disney picture in Xinjiang is just the beginning of such a phenomenon of blockbuster making in the region. It was a transnational production which entertained the world on the Disney+ streaming platform, while we were under lockdown in the four corners of the world, unable to see further than our television screen. Secrecy and silence on the crackdown in Xinjiang is a matter not only of the Chinese Communist Party but also of complicit multinational companies like Disney. After Disney’s former chief executive met with Xi Jinping in 2016, and the subsequent opening that very year of a Disney theme park in Pudong, Shanghai, why not make Xinjiang the next venue for the eleven million visitors of the American attraction in Shanghai?

What a world this would be.

No, what a world this is. Yes, we had better use the present tense, because here, the dystopia does not have to arrive, it has long been!

Entertainment next to the internment of millions. Unlike what we might imagine, this is entirely possible, because it is what is happening today. One day, to our surprise, we learned that there existed a ski resort less than a hundred kilometre outside of Urumqi. Once we drove through the city’s security checks in the periphery, where we were interrogated on our motivations to exit the city and were, once again, registered in a police database; we found the brand new ‘Silk Road resort’ its infrastructure running under its capacity, scarcely populated by a few hundred enjoying the slopes and their distant views of the mountain ranges and the white snow coat atop. Even there, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, a short break from the slopes would find us looking straight at Xi Jinping, on an embroidered carpet hanging above a window at the wall. Surely this prayer rug was not made for … Indeed, it is doubtful that it was turned toward Mecca. It’s rather sure that it was turned, though it was not lying on the ground, towards Beijing. We hence discovered that Xi is everywhere, not only on the massive LED display overhanging a crossroad in Kashgar, or in the museums of Urumqi standing in the middle of dozens of children. But also on a prayer rug, something which we had not found in Xinjiang up to that day, probably due to their disappearance from use. The prayer rug has been given a new function. They can serve as rugs for daily prayer to the state, as well as for recitation of more ‘vernacular’ sorts of slogans, to be displayed even in this restaurant dining room.

Never too badly welcomed

Never too badly welcomed

The Uyghur style of architecture and traditions are disappearing, as are the beards of the few old men left wandering in the streets of those dehumanising cities, but why worry? We can continue living in Hilton hotels and enjoy the exuberant shopping malls, selling and advertising under gleaming lights a commercialised ideal of a culture now devastated. The more police checkpoints guarding the entrances to and exits from the city, the better, so long as it maintains control over the minorities and prevents a Uyghur individual from entering or exiting a city with restaurant knives, even if he needs them for his business.

In Kashgar, it seems as if the city is gearing up for a transition. Its urban landscape has been converted into wide, anonymous boulevards, their sides scattered with homogeneous concrete buildings. The last remaining remnants of the ancient architectural stylings of mud-brick dwellings which constituted the old town of Kashgar, once used to fill in as Kabul for Marc Foster’s ‘The Kite Runner’, are now sealed off behind tall barricades, judged too risky to inhabit. Over two thirds of the old city have already been destroyed since the start of the demolition in 2009.

A few kilometers west, a replica of the old town has been edified. While strolling through its narrow streets passing by the relocated craftsman’s boutiques and restaurants there is an uncanny impression of strolling through a theme park. One night, while walking through one of the district’s few streets, and passing by the innumerable quantity of Chinese flags hanging at the entrances of each residence, we stumble upon a public outdoor projection of a documentary on the Chinese communist revolution of 1949. Such is the entertainment left in Kashgar, aside from the fifteen meters tall Mao statue which dominates the city’s People’s square, along with banners commemorating the 70th anniversary of the inauguration of the People’s Republic.

In Urumqi, the government’s efforts to impose Beijing’s coercive influence is stark. The few days preceding the Chinese New Year implores the deployment of red lanterns at each streetlight, as well as the hanging of the Chinese ideograph for fortune and good luck, as is the norm around China. A seemingly hopeless gesture, at least for the older people in the city, some of whom we witnessed do not speak a word of Mandarin, a reminder of how distant Beijing really is.

Perhaps the last evidence of persisting traditions and local customs can be found in the suburbs and the more remote rural dwellings. A few kilometres out of Kashgar stands the relocated old animal market, once a major trading place on the Silk Road, thanks to the location of Kahsgar on the crossing of the historic routes. A contrast to our previous days in the region, the market provides us with a slight relief, with barely any security cameras or police presence in the midst of the camels, sheep, other livestock and their traders. It may well be here that the feeling of having reached Anatolia is the most obvious. As the French photographer Mathias Depardon both interrogates and reflects in his work “Transanatolia”, are we not here in a region closer to Turkey, than Beijing, as a cultural ‘motherland’?

Last bribes of resilience

Last bribes of resilience

Our presence around the region and in the cities never went unnoticed. Whether this was in the city of Hami, located some six hundred kilometres east of Urumqi, on the way to Gansu province, where on our arrival at the train station, police officers escorted us to our hotel a few blocks away. Only to learn that we are not authorised to stay there, but rather we must stay in another hotel, picked by the police. That same afternoon in Hami, we could not get into a cab without the driver getting stopped moments later to be interrogated by officers about where we were heading. In the city’s bazaar, armed paramilitary policemen patrol the alleys, and the entrances are gated by metal detectors. In Urumqi, once while exiting a metro station, we were stopped by plainclothes police officers who would check our passports. The whole region boasts more than 7700 rapid response surveillance stations, known as the ‘People’s Convenience Police Stations’.

In the city of Yarkand, located some two hundred kilometres south-east of Kashgar, the ‘immigration police’ interrogated us on our arrival, and denied us access to the city. One of the policemen, dressed in plainclothes, took the time diplomatically to excuse himself for the disturbance, with a mastery of English we had scarcely witnessed in China up to that day, arguing that a peculiar sport competition happening that day in town constrained them to maintain public order. To our great disappointment, we were put on a train back to Kashgar, with our first and last glimpse of the city nothing more than a propaganda billboard next to the exit of the station on which was plastered the common slogan: “Strengthening socialism with Chinese characteristics”, and a few construction cranes dominating a landscape of uniform apartment blocks under construction.

Although Paris and other European cities appear increasingly, especially since the reinstatement of the state of emergency in late-October, like urban police states, the daily reality in Xinjiang more closely resembles an urban war trench. In each of those cities the number of police officers patrolling the streets was extraordinary. Police can be seen at each street crossing; and every street corner. Yet, their presence which is predominantly passive, appearing almost futile, and seems to mainly act as a soft psychological weapon.

In Hami, the most heavily policed city of all those we would visit in Xinjiang, approximately every five hundred meters there stands a police station on the street. In all of the cities, as well as in the more remote locations in the countryside, gas stations require a strict security check, with cars often searched, to pass through the gates.

At night, the police presence seems to stay unchanged. In Urumqi, on the public square next to the Grand Bazaar, where some traditional dances still happen during the day, heavily armed police troops patrol the square, running in a bizarre synchronized circuit to combat the frigid cold of January. It is the work of the reader to appreciate the dichotomy, again, between the landscapes and the reality occupying the space. At the centre of the public square of the Bazaar stands a reconstructed tower, which could very well be the product of a theme park. The movement occurring before our eyes is an incessant running of the troops in a deserted public square, contrasting the depicted scene of music in the white stone above. The reality has flipped. The musicians have gone, the policemen reign here now.

Hanification

Hanification

We met a young Uyghur man on the train from Beijing, as we were heading to Urumqi, who was joining his relatives for his once yearly vacation. During our eighteen hours ride to Zhangye, the countless cigarettes smoked and the few phrases exchanged did not suffice to hide our bewilderment at seeing on the back of his phone, under his phone case, his student portrait as a graduate from the PLA National Defence University and his tedious spiel about Chinese foreign policy. His case reflects a wider tendency we witnessed in Kashgar. Unlike Urumqi or Hami, which were primarily policed by ethnically Han security forces, Kashgar’s police apparatus seemed to be predominantly made up of Uyghurs. The seeming aim of the strategy to turn an ethnic population against its own people, as part of a wider assimilation programme referred to by some as the process of ‘Hanification’. Whereas in 1949 Han chinese accounted for a mere 6% of the population in Xinjiang, more than 9.5 million Han Chinese live in the region today, accounting for over 40% of the population of the province.

But ‘Hanification’ is much more pervasive than this. It is reflected most starkly in the way people dress. Photos from only a few years ago reveal the vibrant coloured designs of traditional robes, headscarves and skullcaps. On our trip seeing a woman wearing a veil was a rare event, and seemingly it was only the very old who kept any facial hair, though even their beards were cut quite short. The old men who occupied their days sitting in the square across from Kashgar’s Id Kah Mosque and hobbling over to make up the tiny remaining congregation at prayer times, wore a type of fur hat lacking any religious connotation unlike the embroidered skull caps they once adorned, which are now totally absent. They, like everyone else, wore drab clothing that would not be out of place in any other Chinese city. The bazaars of the region now too exclusively peddle these garments in the Beijing style, though most of this clothing likely has murky origins from within the region’s ‘Vocational Education and Training Centres’.

Smile for the picture

Smile for the picture

How then should one avoid such a ubiquitous police presence, when from the place of worship to the mobile phone, via Wechat, everybody is under constant surveillance? While it is common in China to exchange WeChat IDs, in Xinjiang, not a single person offered or accepted to exchange theirs. In the endless journey on trains between Beijing and Urumqi or later in January, between Urumqi and Kashgar, we would be faced with an uncomfortable embarrassment and unease when asking for someone’s ID. One afternoon in Urumqi, while in a taxi, the Uyghur driver surprised us when we saw him calling with what appeared to be a brick phone, usually unseen in China. Such are the last precarious ways to get rid of the tentacular tyranny and its countless applications.

In September 2020, Xi Jinping declared: “practice has proved that the party's strategy for governing Xinjiang in the new era is completely correct and must be adhered to for a long time.” In August 2020, the Chinese government’s top diplomat and state councillor, Wang Yi, repeated the tired old declaration that what is happening in Xinjiang region is an internal Chinese matter.

We remember back to this picture, a haunting one which could be found almost anywhere in Xinjiang. How happy they all appear… Are they even human? One sometimes wonders if all of those faces are not deepfakes, the result of artificial intelligence algorithms. Surely only being made by an AI could explain their bright, smiling faces. Yes, this contemporary fresco can surely only be the product of an AI; because, if you think about it, where could we have seen so many children in Xinjiang, gathered like this, and smiling in this way? We cannot recall any such encounters.